It’s okay to be the guinea pig in research

The great Abbey Meyers (Founder of National Organization for Rare Disorders) said in her in book that “when you have a rare disease you cannot sit back and say, ‘Let someone else be the guinea pig.’ If not your child, then whose?” I couldn’t agree more with Abbey’s statement. If we truly want to move the needle in rare disease research, then we are going to have to take some risks, especially if our options are limited. I decided to take somewhat of a risk, by getting on a plane during the COVID-19 pandemic to participate in an observational trial at the University of Iowa.

Understanding trials

Before I dive deeper into my trial experience, I first want to point out the difference between an observational and interventional trial. An observational trial is when a participant is being observed or certain outcomes are being measured. An interventional trial (sometimes referred to as a clinical trial) is what most people are aware of since these are trials where a participant is taking a drug and being observed as to whether or not the drug improves the participant’s health condition (and overall quality of life). There is a higher risk with an interventional trial since studies first need to test the drug for safety and efficacy in a small sample before moving to a larger sample size (Phase III of a study).

Luckily for me, I don’t qualify for any of the Huntington’s Disease interventional studies because I am still healthy and pre-symptomatic. However, that doesn’t mean my voice, along with other young adults’ voices, shouldn’t be heard in the drug development cycle. The reason we need to engage earlier and throughout drug development is to make sure all the hard work the company is doing aligns with the community needs. Without the patient voice, the company will be just another data point to the 90% of clinical trials which fail (mainly due to poor trial design and recruitment).

Participating in a trial

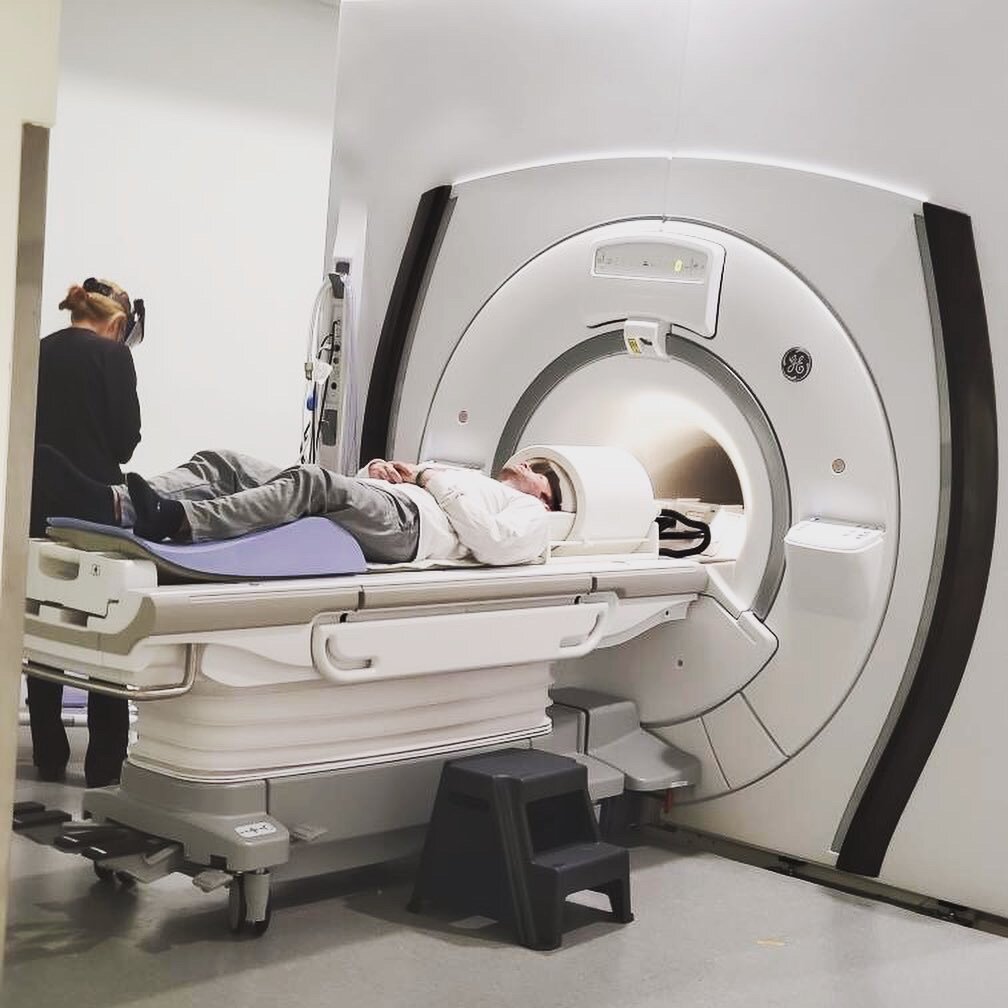

The observational study that I do qualify for is PREDICT-HD 3.0 which involves a full day of cognitive and motor tests, getting my blood drawn, two different MRI scans, and a spinal tap (also known as a lumbar puncture). Originally, I was supposed to go to Iowa in June, but because of the pandemic, we had to reschedule for the beginning of September. Better yet, we did a portion of the study remote to see if it was possible to replicate parts of it to make it less burdensome on the participants.

For the remote section – they sent me all of the materials ahead of time I interacted with one of the research coordinators through an iPad. This took place over two days, where the first day took about three hours and the second day was a little over an hour. The remote section focused on cognitive tests and questionnaires on my emotional well-being. After staring at the screen for three straight hours (in addition to being on my laptop all day), my brain was completely fried. I admitted this to the research coordinator and suggested letting people know ahead of time about avoiding too much time on your laptop prior to the remote section of the trial (or to schedule this part in the morning to get it out of the way).

Getting my first spinal tap

The following week I got on a plane and headed to Iowa to finish up the rest of the study. The study took a day and a half, where I repeated everything I did virtually, along with getting my blood drawn, two MRI scans, and a spinal tap to collect Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Prior to getting on the plane, I told several people about the study and they voiced concern that I was going to fly back the same day as my lumbar puncture. I appreciated their concern since it shows how much they care about my well-being.

Luckily, I confirmed with the research coordinator (and later with other medical professionals) that it is okay to fly back the same day. In fact, they mentioned how most people get side-effects the next day; the most common one being a mild headache. I learned how important it is to advocate for yourself at the doctor’s office and to ask questions when something doesn’t sound right or seems confusing. If I didn’t ask clarifying questions about the spinal tap, then I may have not gone through with it because of my concerns of flying the same day.

Doing a spinal tap wasn’t as bad as I was anticipating it to be. I know some people might think differently, but a majority of it is a mental game. Did it hurt? Yes, when numbing my lower back prior to sticking the needle in me to collect the CSF. Did I see the big needle going into me? Not at all, since I was facing the other way. I also had a veteran doctor who has been doing spinal taps for 10 years. This helped calm any nerves I had before since he explained the procedure in full detail and treated me as ‘Seth’ rather than as a data point in a research study. Having someone willing to listen to you is key to any relationship.

Final takeaways

Based on this experience, I wouldn’t do a spinal tap once a month unless it was the only option on the table and here is why. Not only do you have to take the day off for the spinal tap, but you need to rest the following day as well. Doesn’t sound too bad, until you add up the days and realize that’s 24 days in a year, or almost five weeks I would have to take off of work for this. That’s why it’s important to bring the patient voice earlier in the drug development process so we can gather feedback from them when it comes to trial design.

My final takeaway from this whole experience is how we need to do a better job on educating the community on what it means to participate in a research study. Instead of pointing people to search for answers on Google, we need to have conversations about the importance of participating in research and provide patient-friendly resources to the community. Remember, if we want to move the needle in research, we need people to participate in research.